| Home | Housing | Feeding | Requirements | Breeding | Biology | Books & Links |

Health & DiseasesIntroductionYou may find it helpful to read this page in combination with the Requirements and Water Conditions Page, and also the Frequently Asked Questions. There is a section on the Requirements Page dealing with temperature and the stress it causes, and a section that deals with water flow. The Frequently Asked Questions Page contains answers to specific problems people have encountered. Axolotls are generally healthy animals. Scientific research has found some significant differences between the Axolotl's immune system and many other animals. For example, a limb transplant from one embryonic axolotl to another is usually accepted and the limb becomes fully functional. Likewise, other body parts can be transplanted with equal acceptance. In the mammal, however, rejection occurs sooner or later because the body does not recognise the transplant as a compatible body. The mammalian immune system will seek out anything that differs genetically from the main organism (the so-called auto-immune response). Aside from being able to overcome this side of immunity, the Axolotl's immune system copes with bacterial and viral attack in a similar manner to that of most vertebrates. That being said, the health of an Axolotl is dependent upon how it is treated by its owner. Good captive conditions are described on the Housing Page. Under the conditions described there, it is very unlikely that an axolotl will succumb to disease. Nevertheless, ill-health can occur, and it is important that the hobbyist be equipped to deal with problems, if and when they arise. Stressed animals, whether they be axolotls, dogs, cats, or even people, are more likely to fall sick than comfortable animals. The most common stresses that lead to disease in axolotls are water flow (too powerful a filter in your tank) and temperatures over 24 °C. Other stresses include foul water (the result of inadequate water changes), sudden temperature changes, untreated tap water, parasites, and other tank companions (such as fish). Water quality is probably the most important consideration when it comes to your animal's health. Ammonia or nitrite build-up from inadequate biological filtration (or, in an unfiltered aquarium, lack of regular water changes), can be fatal in a matter of days if left unchecked.

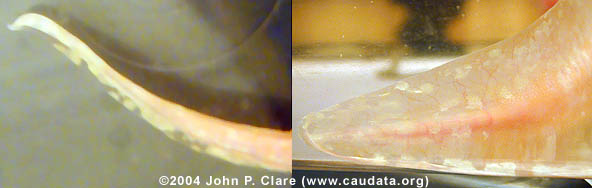

Please note well: Aquarium fish remedies can be toxic to axolotls and it is inadvisable to use them without first consulting an expert. Amphibians absorb chemicals very easily through their skin and it is quite easy to accidentally poison your axolotls with remedies. For example, Sterazin and Protozin from Aqualife are toxic to axolotls. Anything containing metals such as copper or manganese should also be avoided. Two of the most common compounds used in aquarium medications are malachite green and methylene blue. Malachite green is very toxic to amphibians so avoid anything that contains it. Methylene blue is safe to use with axolotls, but as always, try to use the minimum dose. There is a list of reportedly safe or unsafe treatments at the end of this page. For this page, I've divided health problems into four categories: fluid build-up, genetic and nutritional problems; wounds; bacterial and fungal problems; parasites. Fluid Disorders, Genetic and Nutritional ProblemsPhysical problems, such as fluid build-up (edema and ascites), and abnormal cell growth (tumours), are sometimes encountered by the hobbyist. Some of these physical problems are the result of genetic abnormalities and there is usually little that can be done aside from letting nature take its course. Some books recommend draining the fluid with a hypodermic needle but this should only be done by a vet. Fluid build-up can be caused by heart damage, kidney problems, nutritional deficiencies, and even old age. There's not a lot that can be done in such cases, and drained fluid usually builds up again. Some physical problems are related to nutrition. Caudates (a term used to describe newts and salamanders) tend to have difficulty dealing with large quantities of fats and oils in their diet. White worms and tubifex are the most commonly quoted high fat foods. Dog food can also contain a high proportion of oils and fats. When fed exclusively on these foods, occurrences of sclerosis of the liver increase. Other foods, such as mealworms, are quite low in calcium, which can lead to a number of problems. They also have a lot of chitin (a structural protein in insects and some crustaceans) which axolotls can't digest, and this passes through their guts intact. Again, these shouldn't be fed as the sole food but rather as an occasional treat to avoid health problems. Mealworms present an additional danger: they have poweful jaws that can damage an axolotl internally. If you must feed mealworms, it is advisable to crush the jaws of the mealworms prior to feeding. This can be accomplished using a strong forceps or tweezers. If your axolotl develops a nutritional problem, change its diet immediately and try to feed it a variety of foods. Nutritional deficiencies often lead to increased likelihood of the Axolotl succumbing to bacterial or fungal disease. Wounds and Phyiscal DamageThe second category of problems is physical damage, such as loss of a gill or limb, or fin damage. Problems like this usually heal well, as long as the wound doesn't become infected. If an animal is wounded like this, it should be kept on its own in clean, cool water. 100% Holtfreter's solution can be used to reduce the chance of infection, or one can use a teaspoon of salt in 2 litres of water as a substitute. Strangely, wound healing seems to occur more rapidly at lower than normal temperatures. One would assume that the relatively higher metabolic rate caused by a higher temperature would result in faster healing, but this doesn't seem to be the case in axolotls. Lower temperatures (5-15 °C) seem to be a general panacea for axolotls. Sometimes axolotls and larval tiger salamanders are bullied by tank mates in pet shops and can lose most of their gills and some of their limbs. This may seem horrible, but they usually recover quite well if kept well fed, cool, and in good conditions. Bacterial and Fungal ProblemsThere is a list of reportedly safe or unsafe treatments at the end of this page. Bacterial problems make up the bulk of the diseases from which axolotls suffer in captivity. These are mainly opportunistic organisms and the real cause of the problem is usually poor husbandry, or other stresses. A common symptom of stress is that animals will go off their food, or eat very little. They may also suffer from deterioration of the gills. If left unchecked, this stress inevitably leads to disease. Unfortunately, diseases in axolotls, particularly those caused by viruses, have hardly been studied. Aeromonas hydrophila, one of the "red leg" bacteria, is one the most common diseases that axolotls can suffer. It is septicemic, i.e. it can be widespread in the body because it is carried by the blood. Common symptoms are red patches on the limbs and parts of the body. Other bacteria such as Proteus, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Mima, and Alcaligenes, have been found to affect axolotls. Salmonella is also known in axolotls and it is almost impossible to eliminate from effected animals as it becomes resident in the digestive tract. Treatment for most bacterial problems is best left to an expert, but the hobbyist has some means at his or her disposal. Obviously, changing the water is a good idea, but 100% Holtfreter's solution can also help to reduce bacterial numbers in the water and to aid osmo-regulation in effected animals. Antibiotics can be used in axolotls and the the most reliable form of antibiotic delivery is by injection, but this should usually be left to an expert. One form of potentially deadly bacterium that can be treated quite easily if caught in its early stages is Chondrococcus columnaris (commonly called Columnaris). This is a white fungus-like disease often confused with Saprolegnia, a common water-bourne fungus. Animals tend to lose their appetite and become sluggish, and then become covered in white/grey patches of bacteria. It's easiest and best to treat while still in its early stages. One treatment recommended by Heather Eisthen on the Urodeles newsgroup is to dip the effected animal in sea water for 10 minutes a day for three days in a row). Holtfreter's solution in higher than normal concentrations is also effective against Columnaris, as is the use of a salt bath. Place the animal in a salt bath for about 10 minutes once or twice a day. A salt bath is prepared using 2-3 teaspoons of salt (table salt, cooking salt, or iodized salt, but not "low" or "low-sodium" salt) per litre/two pints. Don't leave the Axolotl in the salt bath for more than 15 minutes each time, because the salt will start to damage the Axolotl's skin and particularly its gills. Of course, this is all useless if the animal is still under stress when put back in its aquarium (strong-flowing water, high water temperature, bad water quality, etc....). Saprolegnia, the most common sort of true fungus found in freshwater, can be treated by similar measures as Columnaris and this fungus is only rarely fatal, if treated early. If your tap water has chloramine, this can be used as a treatment for fungal problems. Bathe the wounds or immerse the animal in the water for a few minutes each day, as you would with a salth bath. Fungus can also affect eggs, and effected eggs should be removed if feasible, because the fungus can spread to other eggs quite quickly. In all cases of disease or stress, isolation of the effected animal is strongly recommended and a few weeks in cool water is often helpful to speed recovery during and after treatment. Please note well: Salt solutions can do great damage to the gills of axolotls, leading to bleeding and shedding of gill fimbriae, so don't subject an axolotl to high salt concentrations for very long periods at a time. Mercurochrome is an antiseptic/disinfectant available at pharmacies and can be quite effective when treating bacterial and fungal problems. The former Indiana University Axolotl Colony recommended adding just a few drops to tint the water orange, and change the water frequently. 2-4 ppm (parts per million, i.e. 2 to 4 grams per 1000 litres of water) is the dosage recommended by Peter W. Scott. The University of Mantioba (posted on the Urodeles newsgroup and also the former Indiana University Axolotl Colony) used Nitrofura-G, a compound of Furazolidine, methylene blue and potassium dichromate, to treat skin infections, minor fungal problems, gill fuzz, red sores, and skin irritations. They say it is available from aquarium stores. They use it in the recommended dosage of the manufacturer and find that animals improve dramatically over three doses. Furazolidine is an anti-microsporidal (somewhat effective against protozoans and fungi). Methylene blue is a generally toxic chemical that is toxic to most organisms to some degree. I'm unsure about the toxicity of potassium dichromate. In the late 90s I encountered my first axolotl that suffered from a septicemic bacterial infection (I am unsure of the identity). Susan Duhon and Sandi Borland at the former Indiana University Axolotl Colony recommended treatment by injection of antibiotics (specifically gentamicin or amikacin, both aminoglycosides). This was done with a dose of 5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight (a typical adult axolotl weighs between 150 and 300 grams). The antibiotic was diluted with physiological saline to about 5 mg per ml and about 0.1 ml was injected "interabdominally" (see the photos below). A 1 ml syringe was used with a "25" needle. The animal was treated in this way four times, once every 48 hours. The following photo-diagrams show where to inject the animal (they are based on some sent to me by Sandi Borland).

I have also heard of at least one instance of bathing newts exhibiting early signs of bacterial problems, for 10 minutes in gentamicin (0.2 ml veterinary gentamicin solution per litre of water) resulting in recovery of animals (thanks to Patrick Steinberger for passing this on). This last procedure might be safer than injection for very small axolotls, though it is surely much less effective than injection, as it relies solely on absorption of the antibiotic through the skin. Don't forget to consult the list of reportedly safe or unsafe treatments at the bottom of this page. ParasitesAlthough I've no experience of bait minnows and bait goldfish, apparently they are often rife with parasitic protozoans like Hexamita, Opalina, and ciliates (from Developmental Biology of the Axolotl and other sources). Internal parasites can be treated with flagyl (metronidazole) (Developmental Biology of the Axolotl recommends 500 mg per 100 g of food for three to four feedings). Protozoan parasites such as Trichodina and Costia can cause axolotls to secrete excess skin mucus. Affected axolotls can be treated with mercurochrome, as described above for treatment of bacterial infections. Salt baths (see above) can also be used. Peter W. Scott indicates that Vorticella, another protozoan, can be treated with a 1:1500 glacial acetic acid solution. Vinegar contains dilute acetic acid, and if diluted by about a factor of 100 or so, it can be used with some success. I've also used it on aquatic turtles for treating fungal infections and it works very well. I've yet to encounter parasitic roundworms (nematodes) in axolotls. Peter W. Scott recommends consulting a vet about internal infestations of roundworms and the possible use of levamisole injections. Panacur can be administered to salamanders at a low dosage, and is quite effective against internal worms. I have had problems with free-living flatworms (Platyhelminthes). These can attach themselves to axolotl skin and they seem to like the mucus secretions of axolotls. Magnesium sulfate (part of modified Holtfreter's) seems to be very effective at reducing their numbers. Combined with the routine siphoning of individual worms out of the tank, double doses of Magnesium Sulfate (double its concentration in modified 100% Holtfreter's solution) should wipe out the problem in less than a week, and it's safe for axolotls at this concentration. However I'm not sure if this treatment is effective against gill and body flukes (Dactylogyrus and Gyrodactylus). List of Reportedly Safe and Unsafe Remedies/TreatmentsI am unaware of any commonly available aquarium remedies designed specifically for amphibians. Many medications, treatments, remedies, etc., sold for the treatment of aquarium fish are toxic to amphibians, not to mention some aquarium fish themselves. Many products don't list their primary substituents due to fear of competition from rival companies. They are also loathe to print the contents because it means they can't make extravigant claims as to the efficacy of their products because most of the chemicals used are well known as are their activities. One the springs to mind is simply methylene blue... I've drawn up two lists of some products that are commonly available for treating aquatic diseases and problems. The first is a list of those products (or ingredients in common products) known to be overly toxic to amphibians. The second is a list of products that are either known to be safe to use, or are "relatively" safe to use. As I'm sure you'll understand, I can't take responsibility for any use of one of these sanctioned products and subsequent loss of livestock. I've only made this list to save as much hassle to others as possible. I try to constantly add to these lists, so I welcome any contributions/information. Just because a product is not listed in either list, please don't infer that this means it's safe or unsafe to use: it simply means I haven't used it, never heard of it, or have no knowledge of its effects. If you are unsure about a medication/treatment and it's not on this list, I recommend that you first ask about it in the Axolotl section of the forum at Caudata.org. Please note: A name in brackets is the company that manufactures the product if I know it. A dash is followed by an explanation of the toxicity. List 1: Unsafe and "Toxic" Products

List 2: Safe or Relatively Safe Products

Unless cited in the Acknowledgements, all text and images are ©1998-2019 John P. Clare. All Rights Reserved. Bookmark Axolotl.org with:

What are these? | ||||||||||

reddit

reddit Facebook

Facebook